At this point, on 12 October 1943, Elmore Jenks begins to record his memories of fighting in New Guinea, which took place a year earlier.

At this point, on 12 October 1943, Elmore Jenks begins to record his memories of fighting in New Guinea, which took place a year earlier.

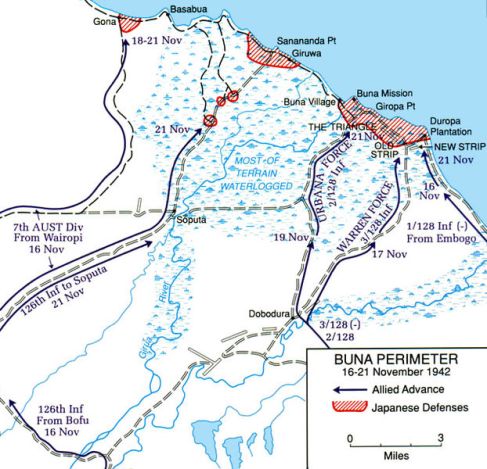

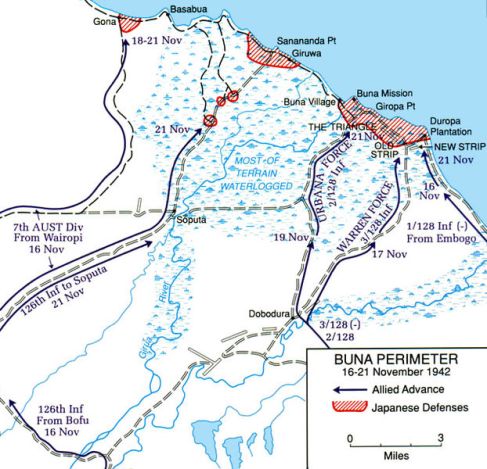

The battle of Buna-Gona, 16 November 1942 to 22 January 1943, was a U.S. and Australian campaign to force the Japanese out of strategically indispensible New Guinea.

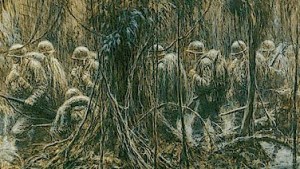

While not privy to high level strategic planning, Elmore clearly senses what historians have confirmed: that poor intelligence led Allied Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur and Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger to underestimate the strength of the Japanese occupation forces. When the allies attacked on three fronts, they were effectively blocked by Japanese defenses commanded by Lt. General Hatazō Adachi.

Prodded by MacArthur to take personal command of the campaign, General Eichelberger belatedly realized the difficulty of wresting the island from Japanese forces. The majority of U.S. troops, including Elmore Jenks, had malaria and other tropical illnesses, and were struggling to advance without the support of requested tanks and artillery. When this support was finally provided, the allies captured Buna on 2 January. General Eichelberger compared the casualty rate to the stunning ratios of U.S. Civil War battles. The number of casualties, killed and wounded, at Buna, exceeded the Battle of Guadacanal by a margin of three to one.

General Adachi (Internet Photo)

I got an inspiration tonight and I thought I’d add to this. I think if I ever try to disseminate the information herein, I’ll sure have a new job. Rather than putting everything in chronological order, I’ve written everything as I think of it or remember it.

I was thinking tonight of New Guinea.

We sailed from Brisbane on 15 November 1942. That was nearly a year ago, after we had been alerted several times for dry runs – tore everything up, issued supplies, packet up, slept in pup tents – and then didn’t go.

But we knew we’d be going soon because the 126th had already flown on up. The regiment left from Camp Cable and went to Brisbane in a convoy of over 100 trucks. It was quite a trip, and we went straight to the ship.

We sailed on a little tramp steamer, a relic of the China seas and rivers in the days of piracy. We sailed under the Australian flag, with a British captain and a Chinese crew.

The trip was quite uneventful. It was quiet and calm. George Bralick and I shared a small two-feet by four-feet cabin. Actually, it was about six-feet by eight-feet, with a small sink and water stand. The entire battalion was on the boat and it was rather crowded. The officers ate in the ward room, which was small but had tables. The food was poor.

We stopped in Townsville and the ship stayed in the harbor for a couple of days. No one went ashore except a chosen few to purchase rations. We did calisthenics and muster every day on board. One day we had a gratuitous issue of PX supplies.

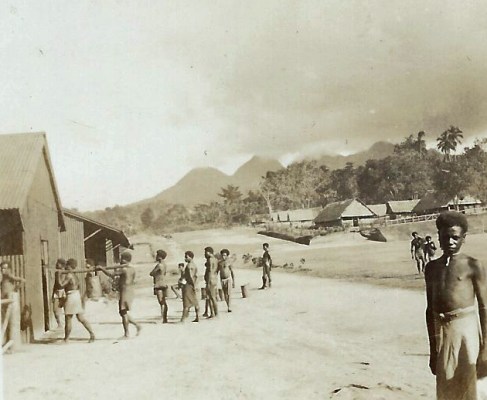

We arrived in Port Moresby on Thanksgiving Day (1942) and transferred to an Australian Corvette in the harbor, which took us to the dock. We were in full gear and battle dress. From the rte, we loaded into trucks and were hauled to our bivouac area out about 12 miles from Moresby.

The town looked pretty badly bombed and all the civilians had been cleared out. Our bivouac area was out past Ward and Seven Mile Dromes, in a rather flat area not far from the beach. For lunch, we had a sandwich made with some kind of ground eat from a can. It was nearly dark by the time we were settled and fed in our area and got our pup tents pitched.

At night, it was pitch black. It started to rain, and it was the hardest rain I had seen yet. My tent fell down in the middle of it, mosquito bar and all. I just pulled the sleeping bag over me and tried to sleep, but I had to get out and straighten the tent up. I got soaked in the process.

The rain lasted about two hours. After that, the moon came out from under the clouds. With the moon came the Jap bombers, three of them. They were dropping bombs on one of the nearby air strips. They weren’t coming very close to us, but we didn’t know that at the time. Out anti-aircraft fire was going up and shrapnel fell all around us. Finally, the planes were picked up by our search lights – there were three of the high up in close formation. We should have been safely sitting in our fox holes, but it was a pretty sight and we stood watching them, hoping to see a hit. It was an interesting sight, and just before the lights went out it seemed one of the planes was hit. We couldn’t be sure.

After that I went back to a damp bed on the hard ground, and hundreds of mosquitoes swarmed around me looking for a meal. My first night in New Guinea was not the most pleasant.

The next day, things looked better. We had a few more raids over the next few days but nothing dropped very close.

The days were exceedingly hot, and often we went swimming in the nearby ocean, sometimes twice a day. The swimming area was enclosed by barbed wire to protect us from the sharks, and often the water was uncomfortably hot. We noticed many barbed wire defenses along the shore, placed there to protect us against an expected invasion.

We often had some hard rain showers at night, and occasionally during the daytime as well. We could get a Jeep every day to run around in, draw supplies, etc., and I did a lot of the driving myself.

After we had been there three or four days, we started taking morning hikes. At first we hiked a half hour out and a half hour back, but later we extended that to two hours each way. We took all our equipment with us, and that was a job, but I guess we got used to it all right. Even so, there was always someone who couldn’t make it all the way.

During the third week we fired on a make-shift range, using all our weapons except the mortars.

The Third Battalion started moving out the second week, bit by bit. They would load up in trucks in the morning with all their equipment, and in the afternoon some or all of them would come back again, depending on how many planes and if they were able to get over the hump.

Bad weather held us up much of the time, and some days they were not able to make any trips at all No unit ever got over completely at one time, and as a result, part of a company or platoon might be fighting at Buna and the rest of them would be waiting at Morebsy. Some units made five or six dry runs and it was sometimes a week before a company was all together on the other side.

The Third Battalion was followed by the Second, and finally by the First. Dry run after dry run. Our chow was fair – sometimes good, sometimes bad. We had an enormous amount of tea, and took salt pills and also five grains of quinine.

Most of us went around with practically nothing on for the first three weeks. I spent most of my time in a pair of cut-off pants and tennis shoes. Finally, though, we were made to wear shirts and pants all the time.

Most of us went around with practically nothing on for the first three weeks. I spent most of my time in a pair of cut-off pants and tennis shoes. Finally, though, we were made to wear shirts and pants all the time.

At night, the mosquitoes were terrible. They came over us like a blanket.

Around 20 December 1942, the pyramidal tents were taken down and the company moved closer together. The First Battalion was the only one left. We saw a movie once or twice a week, and often we had to hold it up for an air raid or alert. The rest of the day, after the morning hike, I spent swimming, reading, writing, ort censoring mail.

[Listening as I read aloud, Dad interjected: “I was the mail censoring officer. Mostly I had to cut out references to where we were located. I don’t know how likely the enemy was to use the GI’s mail for intelligence gathering, but that was my job.”]

On 23 December 1942, the trucks came for us. The day before we had an inspection by the battalion commanding officer and were told how we were to roll our packs, board the plane, etc. We got the impression that we were to step off the plane in front of the commanding general and everyone had to look just alike and immaculate.

That day Captain Lewis and five men from Company Headquarters got off and the rest of us came back – not so far this time, but to a new area. We had another dry run on 24 December 1942 and we saw another movie that night in the rain.

Every evening the Fortresses and Liberators (aircraft) would take off for their nightly missions. They took off right over us and we would count them going out. We’d count them again when they came back around 9 or 10 p.m., and not all of the would come back.

During the day there would always be some P38’s, P39’s, P40’s, A20’s and other smaller planes about. We saw one fortress crash into the water about a mile off shore one afternoon. For some reason, it couldn’t get far enough into the air.

Christmas

Lockheed light bomber (Internet photo)

On Christmas Day 1942, we went to the Drome again and loaded up. There were C47’s and Lockheed two-engine light bombers. Major Schroeder, Lieutenant Hughes, their orderlies, myself, and four men from my weapons platoon loaded on one of the Lockheeds.

We taxied down the runway and hooked a wing on the way up, but there was no damage done. We took off just in time to miss a plane coming in.

It was my first plane ride, and what a feeling it was. Our pilot was a young Aussie lad, and he had one Aussie gunner in a top turret mounting twin light .30 caliber guns.

The ground quickly faded from normal sight, and we were soon climbing fast, straight for the gap. The ground sure looks different from the air. We started over the Owen Stanleys, headed for what we didn’t know. It was cold up there and we went through the gap with feet to spare on each side and underneath.

We were in the air at last; I think it was about 9:30 a.m. We didn’t know whether we would get over the gap or not. The weather reports were good, but the storms gather so quickly in the mountains that the route might become impossible at any time. We climbed and climbed to get through the gap, and the air was chilly. Finally we made it. The trees on either side looked only a few yards away, and the tree tops beneath looked closer than that.

[Dad seemed to be reliving the experience as I read this excerpt to him. “I could have reached out and grabbed some trees,” he said.]

After we finally made it over the gap, we came down just over the trees and the pilot opened up and we sped toward the coast. We didn’t take any chances on there being any Jap planes flying about.

There was another plane about a quarter of a mile behind us, and another about the same distance behind that. As the terrain became more level, we could see strips of jungle along the streams below, and open fields of junai grass. We couldn’t actually see the streams, except for the ones that were coming through the mountain, which were fresh, cold, and clear.

Finally, as we neared the landing strip, they told us to move toward the front of the plane. I had already counted three strips that we had passed – we were to be taken as far as possible toward the front because of all the heavy weapons we had to carry. The rifle platoons landed about 10 miles further back at Popendetta.

Finally we banked steeply – I looked out the right window and felt I could reach out and touch the grass, and from the left window I could see the clouds in the bright blue sky – and came in for a rather smooth landing on one of the Dobadurra strips. The strips were simply runways cut into the grass.

We hurriedly put our equipment on and unloaded from the airplane. We were told to get off the field in a hurry as there might be Jap planes over head, looking for a good strafing target. The strip was about 50 yards wide and it was made from matted cut junai grass, and we cleared off it in a hurry.

The grass at the edge of the strip was about as high as our heads. We found a road ads followed it to a small village where we found Captain Patterson, his first sergeant, and several enlisted men. They had fixed up the native huts and were living in them.

It was nearly noon, and we were hungry, so we sat down to eat some C rations and began to talk things over. We were given some canned pineapple which tasted pretty good.

We learned that we landed at the smallest of four strips at Dobadurra. My Christmas dinner consisted of a can of meat and beans, some hard biscuit, and a couple slices of pineapple.

April 13, 2017. Dad died 18 years ago this month. He was one of 16,112,566 men and women who served in uniform in the Second World War. This year, less half a million of those vets are left to tell their story.

April 13, 2017. Dad died 18 years ago this month. He was one of 16,112,566 men and women who served in uniform in the Second World War. This year, less half a million of those vets are left to tell their story.